When a young girl's father forbids Japanese in their American home, she finds other ways to carry her heritage: in memories of summer festivals, in songs shared with forest spirits, in the wind that follows her across the Pacific. A tender meditation on childhood resistance and the things we choose to keep.

By

— Silent No MoreNo jurisdictions, towns, or precincts. For the almost four-year-old child, Japan is one continuous adventure of the senses—wet smell of rice fields, shiny, smooth, stone streets after rainfall, panoramic skies challenging farmland after farmland to see which of them will go on forever.

The little girl sits in the back of the car, window down, wind blowing through her hair. Her mother had tied it back so it wouldn’t tangle, but the girl removes the tie.

How can you play with the wind when it can’t race through your hair? She leans out the window and breathes deeply.

She reminisces about how the summer festival, last week, enticed the girl into a world of magic. It appeared out of the night—the music, the lanterns, and the dancers wrapped in kimonos, faces painted white, hiding and reappearing behind silken fans tracing full and half circles in the air.

The girl gasps. She realizes a beautiful dancing woman is a man. He tilts his head to the side and looks down from beneath thinly drawn eyebrows, catching her surprise, and tosses an almost imperceptible smile back to her on painted red lips.

She smiles back, delighted to be part of, what is to her, an agreed-upon secret.

Running back to find her mother, she almost crashes into a barrel of water filled with splashes of gold. Small fins and tails in motion cut water with quick turns, laughing at paper nets. How she wants a goldfish of her own!

She thinks of the giant koi in her uncle’s pond, great spectacled water dragons, in slow motion, gliding toward her. Miniature pine trees and oak along the water’s edge invite the girl to sit next to them. In the silence together, they remind her though she is little, she is still mighty.

The fish in the barrel are not like the gliding dragons. Darting streaks of motion and color, they dodge the dissolving paper net clutched in the child’s hand. She fails to catch even one.

But her big brother can, and he does. Anticipating its move, he scoops one up, flips it into a water-filled paper cup, and hands the captive fish to her. At the night’s end, she leaves the festival, careful not to tip the cup on the way home and making sure to feed it before they leave for a road trip the next day.

*

Sitting in the back of the car with her brother, she doesn’t know where they’re going. Her parents talked about it earlier that morning, but she pays attention to only the important things.

Like the way wet fields carry the sky in its waters, how black and gold koi look like dragons with wings, and how thoughts can drift among the bonsai in a garden, hugging a pond as easily as mist can linger upon trees jutting out of mountains.

The wind pushes against her face like a hard kiss, the kind a mother would give her child when she’s relieved it’s all right.

The car makes its way to its destination, but it’s her thoughts that carry the little girl into the mountains. They bend themselves down and lift her up, taking her to the waterfalls on the sharp inclines, to the shadows beyond the trees, and the occasional bird that flies out of nowhere, letting her know she is on the right path.

The mist and wind catch themselves chasing each other in her hair. She hums one of her own melodies and smiles.

She hasn’t seen one yet, but she believes in the Kodama of Japanese folklore, nature spirits who protect the trees and surrounding environment, watch over her. They sit with her when she communes with nature and sings her songs, a mix of real and made-up Japanese words. The Kodama understand her songs and they love her.

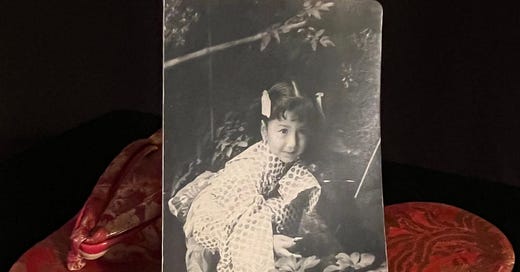

So much so that these moments refuse to leave her, even when the time comes for the family to pack their lives into suitcases. When they board the plane, the little girl carries more than her silk kimono and her fancy red geta sandals with the jingly bells in their heels. The rice fields and dragon koi and summer festivals, the mountains and mist, the walks on country paths and through city streets, the kindness of her brother, and the wind that chases her across the Pacific Ocean to America, all come with her.

*

In flight and over ocean, between the world she’s leaving and the world she’s approaching, the girl tires of looking out the window for stars that should be closer now that she’s in the sky but are not. It will not be the last let-down to follow leaving Japan.

Decisions have been made for her. She will not speak Japanese in the United States. She doesn’t understand what her father means when he explains she will be in America and needs to speak “only American”.

She also looks more like him than her Asian mother, he says. He’s white, which, to him, is synonymous with “American.” She has to be American or white. Not foreign or different.

She sees by the arch of his left brow and the way he commands her gaze, he’s serious. She will not defy him.

The weight of her lids pulls her into sleep, and the memories of Japan bend so close to her she breathes them in—one by one, kissing her eyes, drifting on her breath to find home in her heart, pilgrimaging to her bones, strumming her vocal folds with story, readying her fingers for pen and keyboard—the festival, her made-up songs, the landscapes, and nature, and the Kodama who protect them.

She sleeps and dreams and lets herself be loved this much.

The plane lands. The girl gets off. Her father doesn’t know. She is different, forever. And she doesn’t know how many times that will save her.

About Demian

Demian Yumei says describing her Asian side is complicated. Growing up, she often heard from her mother, “We are Chinese, not Japanese.” Demian’s mother was born in China, but raised in Japan. In recent years, Demian discovered, through DNA testing, she is not only Japanese as well as Chinese, she is also part Korean. She always felt a strong kinship with China which informed her writings and activism. This new knowledge adds more depth to her personal memories and love for Japan and opens a door to learn about and embrace her Korean heritage.

As a survivor of childhood abuse, Demian has written and recorded a collection of healing songs called For the Sake of Love. She also wrote a children’s picture book, published by Illumination Arts, that is based on the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh, called Little Yellow Pear Tomatoes. She is currently working on a memoir, and when not writing, she and her pittie mix, MJ, can be found hanging out with her grandchildren and grandpups.

Want to submit to Asian Writers Collective?

Read full submission guidelines here. We’d love to read your work.

Thank you, Tiffany Chu, Bakhtawar, and Christa Lei for creating the beautiful and empowering space that Asian Writers Collective is. I appreciate the opportunity to share some of my long-ago, deeply cherished memories. To say it was a pleasure working with you, Tiffany, would understate just how much of a positive experience it was. And it's been an even deeper healing experience for me than I anticipated. With all my heart, thank you. ❤️

The way this is written makes me feel like I’m vividly seeing through the eyes of a young child :)