In a society ruled by gods and men, women find themselves in gilded golden cages, unable to break free, stuck in a continuous cycle of trauma that is passed down through the generations—an inheritance that we must take and hand over to our children.

By

— In-Between LinesOn the sixth day after my birth, my mother left the small window in our room open, a blank sheet of paper on the desk, ready with a pen. At midnight, Brahma, the creator and God of destiny, would visit and write my future on that paper. The next day, the paper would be folded and given to a priest at a temple, thus acquiescing to the god’s wish. My destiny had been written before I realised that I was no longer in my mother’s womb.

There were many traditions that followed my birth, all aimed at pleasing various gods. We lived in faith and fear, moving from one ritual to another in the hope that our lives would be made better, our future brighter, and our marriage fruitful.

Just before my third birthday, my parents, grandparents, and one-year-old brother travelled to Varanasi for another necessary ceremony. We were to get our baby hair shaved off by a priest. The hair from the womb was considered inauspicious and full of negative energies and influences from our past lives. In shaving our hair, we were cleansed and purified—free from the baggage we may otherwise carry.

While my brother was relatively calm, snuggled up on my mother’s lap, I burst into tears the minute the sharp blade touched my hair. I saw the locks fall all around me—a waterfall of jet- black curls. My father patted me gently in an effort to soothe his terrified child. My mother had vanished.

I went to school wearing a hat, ashamed and embarrassed at my bald head. No one told me that my sins had been washed and I was now a pure, innocent being ready to begin a new life.

Between the ages of five and eleven, I was invited to my neighbour’s house once a year to be worshipped. On the eighth day of Navratri—a nine-day festival celebrated in honour of the goddess Durga for killing a demon—it is said that the goddess enters the body of young girls who have not begun their menstruation. I was worshipped as an embodiment of this goddess without the privileges that she would have enjoyed. I had no say in the matter.

Families ruled by men used the gods as a powerful tool to control dissent and discontentment. My family was one such, amongst many, in Calcutta. While men worshipped goddesses in temples and bowed to them in reverence during festivals, the women in their households enjoyed neither adulation nor respect.

The women fought their battles within the confines of their homes. They did not succumb to rage, running into the fields with their swords held high. Their victories were slow and hard- earned, cultivated carefully over the years. They played the long game, giving up their youth, hoping that the small wins would add up to victories for their children.

My mother was one of the many women in our household, a warrior of unimaginable strength and resilience. Her story began when she met my father, as did her decade-long battle with the gods she revered and the men who stood in her way.

This is her story and, in some parts, mine as well.

My parents met in 1978. While floods ravaged West Bengal, Calcutta hosted the National Football Championship. An Indian Airlines flight was hijacked, Indira Gandhi was yet to win her second national election, the Left Front government had just come to power, marking a new era in Bengali politics, and the Calcutta Stock Exchange was established. India’s first test-tube baby, Durga, was born. The first satellite, Aryabhata, was launched, and the first nuclear explosion was tested at Pokhran, Rajasthan.

As India advanced in politics and technological milestones, my parents dated secretly. The world was opening up, and our country was modernizing. But the families of Calcutta refused to change. We remained stuck with outdated values and dysfunctional systems. Dating was strictly prohibited and limited to meeting a man your parents chose, whom you would eventually marry.

Things may have gone differently if not for the accident that changed their life. It was a turn taken too quickly amidst a heavy downpour. We don’t know whether the lorry stopped without warning or if my father did not see it in time. My mother was rushed to the hospital, cut and bleeding all over her face. My father was unharmed.

“Who will marry her now?” my grandfather asked my father when he saw the three-inch cut along his daughter’s face, from cheek to chin. “I will,” my father answered.

The conversation should have led to wedding preparations. Instead, my paternal grandfather refused the match. My mother was not from the same caste or social standing. The marriage could not happen.

My mother refused plastic surgery to remove the scar from her face. She wanted a reminder of the consequences of lying to her parents.

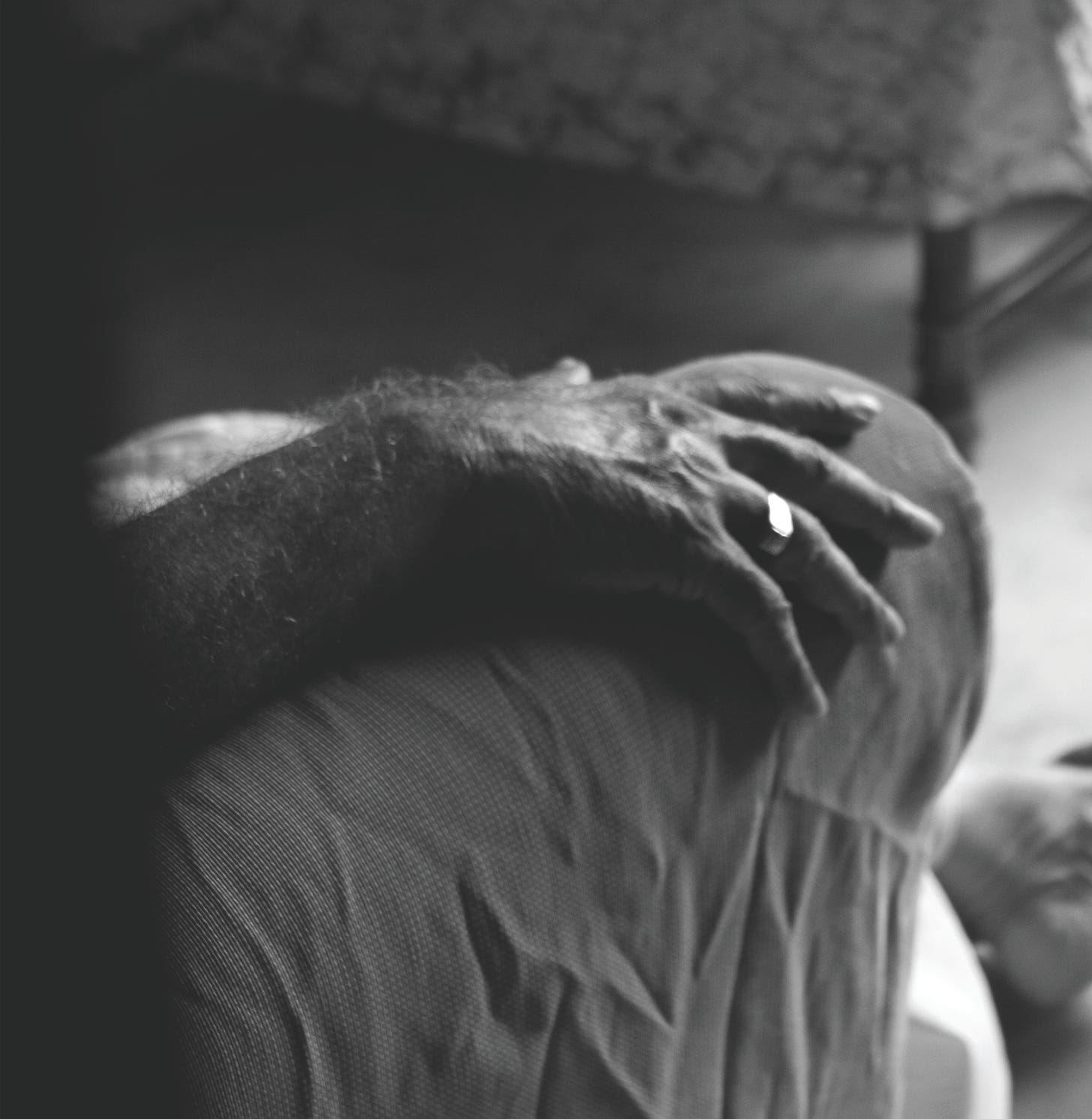

They had almost given up hope when, in 1979, my father’s grandfather asked to meet my mother on his deathbed. His wish could not be denied. As my mother gingerly approached him, he smiled at her and blessed her, placing his hand gently on her head. The match was approved, and as the family patriarch, his word could neither be challenged nor refuted.

The accident set the tone for my mother’s place in a family that was complex, complicated and hierarchical. According to my grandfather, she had jumped the line and made her way in, against his wishes. Her situation as a new daughter-in-law was not favourable. My parents married out of love, hoping that, with time, my grandfather would forgive them. He almost did.

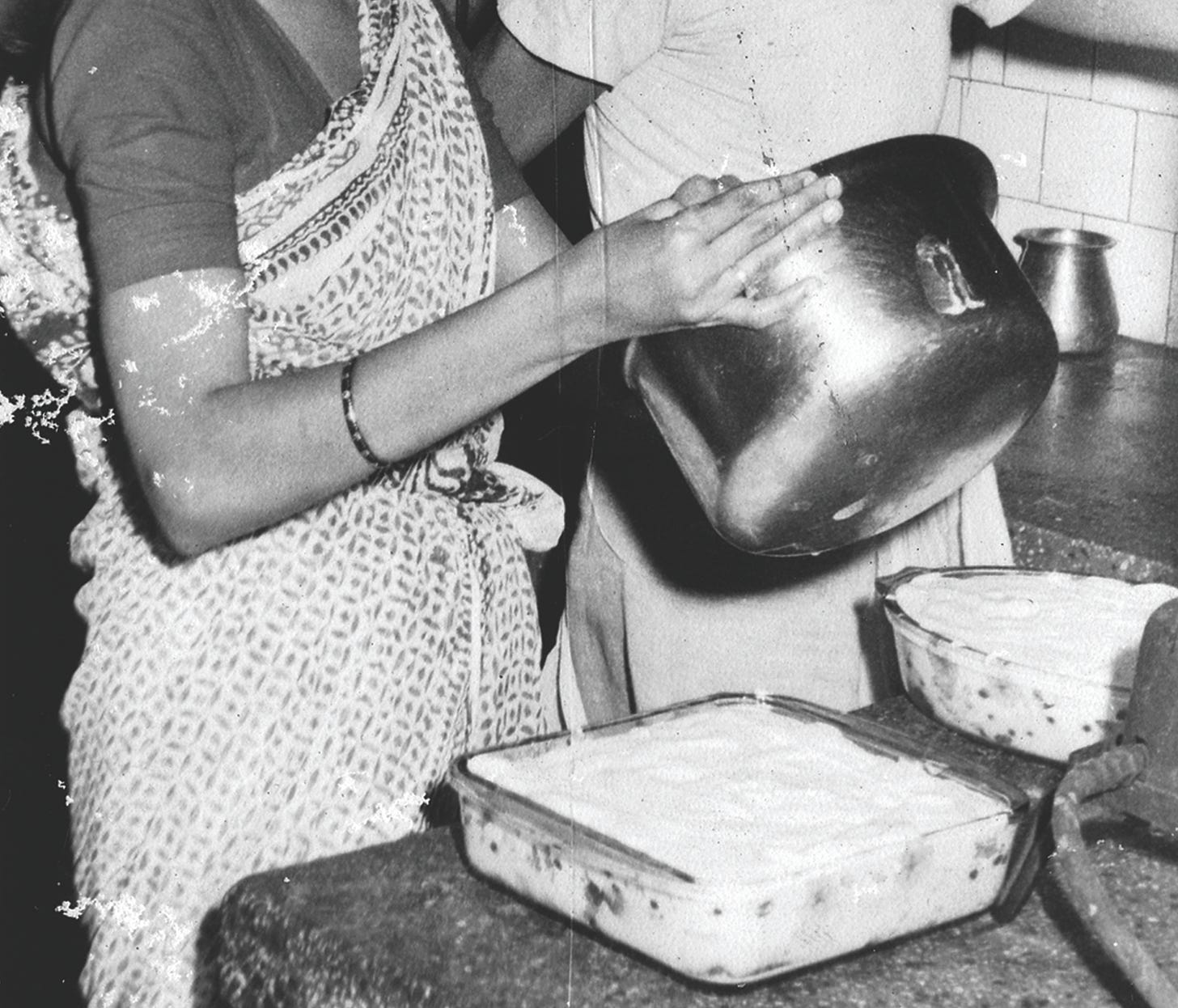

My mother was a dutiful daughter-in-law. She adjusted to the new family dynamics without question. In her opinion, she had wronged them and would have to work hard to be treated as a family member. She brought her love for continental cuisine into a household that had only seen and eaten staple Indian food. She made the first lasagna, pizza, pasta, and baked dishes. The children loved her and flocked to the kitchen often. My grandfather appreciated her effort and bought her a small oven, thus indulging her for the first time.

However, a daughter-in-law’s duties are not confined to household chores. She is also meant to have children to strengthen the bloodline.

Three years after their marriage, the family began questioning my mother’s fertility. Why had she not had a child yet? While children were being conceived simultaneously so that there were always two of the same age in the house, my mother paid no heed to family planning. Eventually, the pressure hit a high note; she removed her Copper-T, and I was born in 1983.

My birth changed everything.

Our family was large. My father had three brothers and two sisters. The sisters were married. The rest of us lived together in a house that could spare only one room for each family of four. We shared the drawing room with a single TV and one landline phone. We ate our meals together, and the women cooked in one kitchen. A separate prayer room was dedicated to the gods and managed and run by the women.

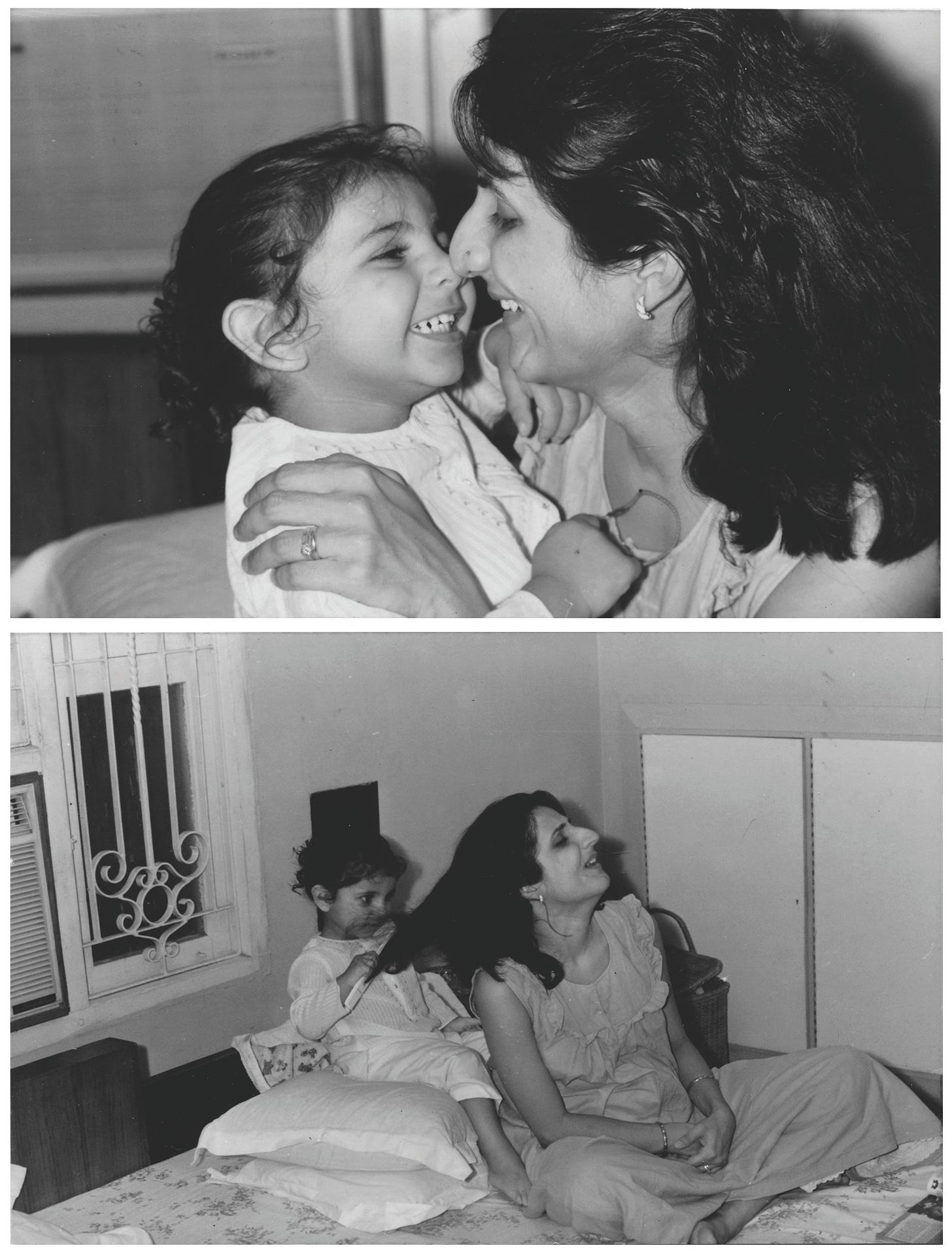

Two years after my birth, my mother produced a bonny baby boy. We were both fair and chubby children in a house of brown-skinned kids. My mother was educated, liberal, and free- thinking. Her ideas were considered radical, and her parenting was often questioned. But she did not budge. When it came to her children, no indulgence was too much, education was paramount, and the arts were necessary for creativity and growth.

My mother loved my father and, by extension, his family. She wanted to be liked and accepted. But when it came to her children, everything else paled in comparison. Her instincts to protect us overrode her logical brain.

We were her greatest source of courage and the reason for eventually being cut off from the family.

My grandfather was a patriarch who ruled his kingdom with an iron fist. We were in the business of making Indian sweets. Our confectioneries were many and well-known. No wedding or event in Calcutta was complete without our delicacies gracing the buffet table or being gifted in neatly wrapped boxes. My grandfather had five outlets. Each son managed an outlet and was paid a monthly salary. All outlets were owned by him, and the final decisions in business were his.

The women were not allowed to work or join the family business and were relegated to daily duties of cooking, cleaning, praying, and managing their children. They were expected to wear only sarees, leaving little to no choice for self-expression or creativity.

My mother quickly realised that her husband’s salary could not support her vision for her children. She needed to earn money on the side. A good lawyer can work around any contract and find loopholes that would benefit the case. Since my grandfather would not allow the women to work, she opened a small business in the garage, hired a tailor, and began taking orders for children’s clothing. No one could find a logical argument to object.

As she grew financially independent, the household grew restless. Cracks began to appear in the near-perfect façade of our family. Eventually, my grandfather closed her small business, citing her unavailability for household duties as an excuse. But my mother did not give up. She started another small business from her parent’s house, leaving after we were asleep at night. The family snitch found out. My mother was caught and the aftermath was not pleasant. She was not allowed to leave the house after dark. My grandmother said the children could not be left alone at night.

My father, encouraged by my mother’s courage, asked for ownership of the outlet he was managing. My grandfather refused. “If you want to run the business yourself, buy the shop from me and leave the house. As long as you are under my roof, my rules apply.” His fists tightened, and he found many ways to punish my parents for their impudence.

The cracks deepened, fissures spreading across the wall like rivulets.

My parents would have borne the brunt of my grandfather’s wrath if he had left my brother and me out of the fight. But patriarchs do not like being questioned or challenged. It began slowly and from within the house.

We were first cut off from the kitchen and asked to cook our own food. My father arranged a makeshift kitchen right outside our room, under the staircase. Next, my mother was banned from entering the prayer room. It was best if the women did not support her.

Phone calls were refused, and messages from friends were blocked. The night curfew continued. My parents could not make a single decision without my grandfather’s permission. Our outings were reduced, and we could no longer call our friends over. They tolerated it, hoping that the storm would eventually subside. I could blame myself for what happened next, but that would make my grandfather not guilty—and that would be far from the truth.

We were practicing for a school play in the afternoon. There were peals of laughter and raucous romping. This was the time my grandfather returned home for his afternoon nap. When he woke up, he lined up my friends and reprimanded us for being unruly and disrespectful. He held my arm in a firm grip and whacked me. “As young girls, you should be seen and not heard.” I was eleven years old.

I remember being angry and ashamed. My cheeks burned with embarrassment and my hands clammed up. My body rebelled, turning rigid, refusing to bend or apologize. I had done nothing wrong. I walked out with my head held high, hugged my friends who were leaving, and then headed to my room to tell my parents.

With a sickening sound, the façade cracked and the wall collapsed.

Two days later, we packed our bags, our entire lives fitting into six large boxes and four suitcases, and left the only home I had known. We were not allowed to take anything else.

The eviction took eleven long years. My grandfather had played a long game too, but his was dirty and filled with jealousy and hatred—a battle of wits, backstabbing, politics, power play, and money. My mother fought hard—for her right to belong, for her right to work, for her right to be accepted and loved. She fought for her children. She fought for all the women in our house who could not raise their voices in protest. She fought for the women in her community and country, a warrior’s cry against systematic injustices that they faced on a daily basis. She fought with the hope that one small win would encourage others to join and support her. She fought so that I would not have to.

Her fights were not bloody or cruel. She did not go into battle with her sword raised high above her head. She did not succumb to rage. Her victories were slow and hard-earned. She gave up her youth, hoping her children would have a better future.

In the end, she lost not because she was not strong enough. She lost because she refused to give up her sense of self, her identity, and her dignity. She refused to change her ways, to fit into a mould agreed upon by the gods and men.

As the gods watched, my mother’s life was scrutinized, analyzed, evaluated, and considered inconsequential. She was discarded, like a rabid dog foaming at the mouth. She was no longer of use to the family—an infection that was best cut at the source, lest it spread amongst the women of the household. If there was one thing my grandfather feared more than the gods, it was radical thought and free speech.

I grew up in a house where your identity, destiny and future are decided by the Gods. You are the gender you were born with, and you carry the burden of its expectations throughout your life. Your birth chart dictates who you marry and when you marry. Sometimes girls are born with inauspicious futures which may kill the first husband they marry. To nullify this, they are married to a tree first.

I am not free from the history that precedes my mother, grandmothers or the women who came before them. The burden is passed to the child in her womb—quelling any rebellion at the formative stages of growth. Our body learns the history of our ancestors, setting the foundation for what we must value and what we must discard.

Today, we call it trans-generational trauma. It takes many years to realize that we are bound to the trauma of our ancestors and many more years to break that cycle, if at all. For those who don’t have the means to work through their own histories, the trauma passes to their children.

I grew up in a world where we worship powerful goddesses and yet prevent menstruating women from entering temples. We hold the womb as sacred, yet find the baby hair that grows in it impure. We worship little girls and yet do not let them decide their future. We keep our doors open for gods to enter silently at night and determine our fate.

My identity as a woman is deeply connected to the shared experiences of the women in my household. They were not weak women. It takes a certain kind of strength to bow to a patriarch and yet hold your head high in the face of injustice, to not break or back down.

I am my mother’s daughter. I have learned to love fiercely and live independently. I have learned to question authority and rigid social structures. I have fought for her and beside her.

We may not always see eye to eye. Where she sees the power of faith, I see worship used as a tool—to frighten or gain power. Where she sees value in old traditions and customs, I see a family that caged a free spirit. What she considers as a compromise, I see as arm-twisting. We are from different worlds, living in parallel lines. We will never find a meeting point, both of us caught in our own cycles.

The difference in our thinking became even more stark when my daughter was born. Here was a chance to break the cycle of trauma. To give my child a life that was her own, free from the fate of gods and the will of men.

On the night we returned from the hospital, my mother insisted that we leave the door open for Brahma to bless and decide her future. I protested. As an atheist, I was determined not to let the shadow of God touch my child.

“This is my only wish. Please let me have this,” my mother pleaded.

“She is not your child!” I screamed in anger.

“She is my granddaughter. The door will be left open.”

I could have fought harder. I could have said no. We could have argued well into the night. But I let it go. I am not sure why. The following day, the empty piece of paper was given to a priest at a temple. I told myself that rituals only hold power if you believe in them. I would protect my child from the whim and fancy of gods, shield her from dated notions of good and bad, teach her to fight and stand up for herself. I would lose a few battles if I could win the big ones.

My daughter is eight years old today - a free spirit who questions openly and rejects without fear. She is not sure if she believes in God. I have left that decision and journey of discovery to her. What she does know is that I will respect her opinion, fight her when I need to, and give her the space and freedom she needs to grow into a beautiful woman. We may not agree on everything, but that is okay.

I sometimes wonder, if my mother had the life and freedom I have now, would she have lived differently? Would she question the faith and customs that she holds so dear? Would she realize the many cages she had built around herself? Perhaps someday, I will ask her.

The identity of women in India is irrevocably connected to their families and guided by caste, class, social standing, power and influence. Your future is decided based on these parameters. And fear is the weapon used by men to ensure that these structures hold strong—a golden empire with gilded cages.

I know that I have many such cages, one locked inside the other. I am aware of my years of conditioning and knee-jerk responses from generations of subservience. And yet, I fight—not for myself but for my child—in the hope that one day, I will break the cycle and free her from my family’s history. My daughter’s future will not be dictated by my past. The men will not tell her how to talk, walk, dress, or behave. The gods will not decide her future. To move forward, we must break the link to our past. To find the key that will open our cage, we must first find our voice. To command respect, we must find ways to love ourselves. Because when we do, the empires built by the men and gods will crumble overnight.

About Samira

Samira is an Indian woman who works and lives in New Delhi. While she runs a communication design studio professionally, writing has her heart.

She writes to understand her history, culture and customs. She write to witness her lived experiences and make sense of her world. She writes because sometimes words are stronger and wiser than conversations. She also writes to open up space for those who have lived similar experiences—perhaps in search for others like her. Samira believes we are not alone in our struggles, our battles and our victories.

Her writing aims to navigate the complex society she grew up in and questions the myriad customs and rituals that surround us as we grow older.

You can also find her on Instagram.

Want to submit to Asian Writers Collective?

Read full submission guidelines here. We’d love to read your work.

Thanks Aayaan. I find no difference in patriarchy - brahmanical or otherwise so it didn't even occur to me. :) My grandmothers story is an interesting one. Perhaps I'll write about it someday!

This was such an incredible piece, Samira.

We have very similar rituals for young children here, and exactly the same treatment for women. I have been struggling to articulate all this as well as you have. Thank you for writing this. I am sorry that these conditions of living for women in our cultures have been normalised, and therefore not given the attention needed to make a change. Kudos to you for doing this for all of us through your art.